In a comment on a Ello post by @dave73, @dredmorbius shares the opening paragraphs of a piece written by Annie Leonard for the WorldWatch Institute’s 2013 State of the World report, “Moving from Individual Change to Societal Change”.

In the paragraph, she refers to this ad:

In one of the most iconic ads of the twentieth century, a Native American (actually, it was an Italian dressed up as a Native American) canoes through a river strewn with trash. He disembarks and walks along the shore as the passenger in a car driving past throws a bag of litter out the window. As the camera zooms in to a single tear rolling down his cheek, the narrator announces, “People start pollution. People can stop it.” This 1971 ad, just a year after the first national Earth Day celebration, had a huge impact on a generation awakening to environmental concerns. Children and young adults watched it over and over, shared the faux-Indian’s grief, and vowed to make changes in their individual lives to stop pollution. That response was exactly what the ad’s creators hoped for: individual action. For the ad was produced not by a campaign to protect the environment but by a campaign to protect the garbage-makers themselves.In 1953, a number of companies involved in making and selling disposable beverage containers created a front group that they maintain to this day, called Keep America Beautiful (KAB). Since the beginning, KAB has worked diligently to ensure that waste was seen as a problem solved by improved individual responsibility, not stricter regulations or bottle bills. By spreading slogans like “people start pollution, people can stop it,” KAB effectively shifted attention away from those who design, produce, market, and profit from all those single-use disposable bottles and cans that were ending up in rivers and on roadsides. As part of this effort, KAB created the infamous “crying Indian” ad against litter.

And:

Framing environmental deterioration as the result of poor individual choices—littering, leaving the lights on when we leave a room, failing to car-pool—not only distracts us from identifying and demanding change from the real drivers of environmental decline. It also removes these issues from the political realm to the personal, implying that the solution is in our personal choices rather than in better policies, business practices, and structural context.

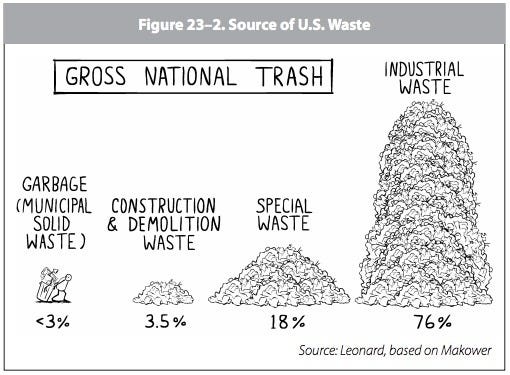

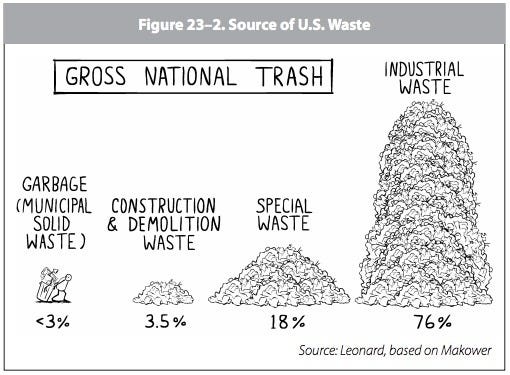

And that is a huge issue. If we focus the bulk of our attention on reducing waste in our kitchens, we miss the much larger potential to promote reducing waste in our industries and businesses — where it is truly needed.

We need to keep our focus on change beyond the level of our individual actions. Society-wide, we need to implement new technologies, cultural norms, infrastructure, policies, and laws.

As 350.org founder Bill McKibben says:

First change your politicians, then worry about your lightbulbs.

Or, in Leonard’s view:

Small actions are a fine place to start. But they are a terrible place to stop.